Dusting off and reconstructing Théâtre Morieux de Paris

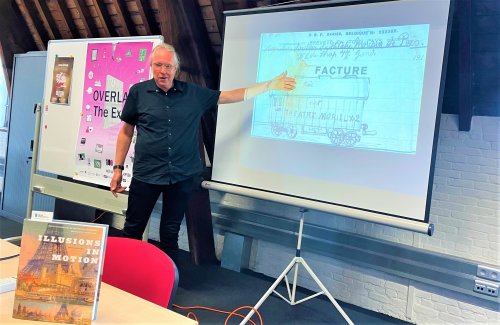

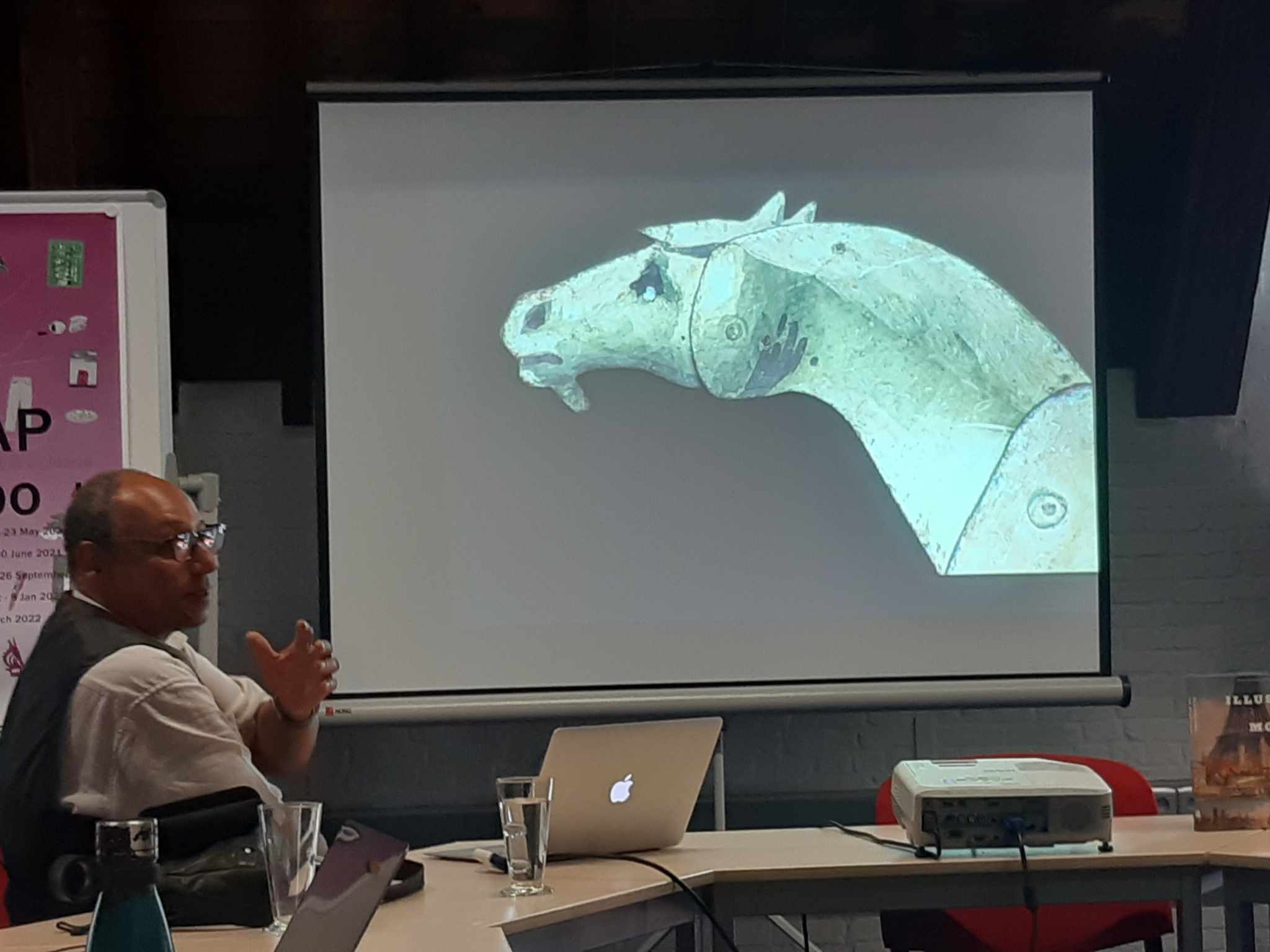

How can we study nineteenth century fairground culture? How do we piece together a historical narrative based on limited and fragmentary sources? Most travelling fairground attractions left few traces, except for fragments in the form of flyers, posters, program booklets, newspaper reports, postcards and occasional photos. But sometimes, miraculous discoveries are made. One happened when Thomas Weynants discovered items from a forgotten travelling theatre at a flea market in Ghent. Weynants and Erkki Huhtamo discussed the rediscovery of Théâtre Morieux de Paris during a visit to the SciFair team in September 2022.

Théâtre Morieux de Paris has disappeared from our collective memory, but in the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries, it was a popular attraction at Belgian, northern French, and German fairs where it drew huge crowds. It was advertised as a mechanical puppet theatre, théâtre mécanique.

An ingenious system of rails, pulleys, and hand cranks made figures of tin sheet move on rails laterally across the stage in front of a painted background. Elaborate moving tableaux were concocted by technical ingenuity.

Other scenes, created by rolling moving panoramas or by projected magic lantern slides, took visitors to surrogate journeys to different parts of the world. At the turn of the century, Théâtre Morieux added cinematographic moving pictures to the variety of attractions fairgrounds audiences were offered.

Traces of a forgotten attraction at a Ghent flea market

Despite its great popularity, Théâtre Morieux fell into oblivion in the early 1930s, as its touring life came to an end. It was abandoned behind locked doors in the same warehouse from where it had left for its tours and where its materials had been serviced. Then, one early spring day in 2006, Thomas Weynants, a Belgian collector and expert on early visual media, made an extraordinary discovery.

At a flea market near Ghent, among a whole bunch of other interesting paper ephemera, a small and fragile 4-part panorama design, drawn in pencil, on the theme of the Paris Universal Exposition 1900 caught Thomas’s attention. Intriguingly, certain details in this panorama were marked as “transparent”. So this was clearly a design sketch for something bigger. He soon realized that the seller had many more interesting things to offer. “This premonition quickly came true after my first encounter with the striking mechanical puppets, moving panoramas and many other oddities among the myriad of ‘remains’ acquired by Jean Paul Favand,” says Weynants.

The trail led to the old warehouse near Gent-Sint-Pieters, where the former Théâtre Morieux’s belongings had been stored for decades. It was only when the relatives wanted to renovate the building that they ordered it to be emptied. A local flea market seller became involved, and some items found their way to the flea market, as well as to Belgian and Dutch collectors. But there was much more. The flea market seller found silent films marked Gaumont and Pathé, and contacted film archives in Paris. They showed immediate interest, and also bought piles of colourful film posters that had once promoted the offerings of Théâtre Morieux.

French museum director buys up collection

That is when the Parisian Jean Paul Favand got wind of the venture. The former antique dealer and great fairground collector, also the owner of the exuberant Musée des Arts Forains in Paris Bercy, contacted the flea market seller and then managed to trace the family who owned the warehouse. He bought everything that remained, which was a lot. Many objects, covered by layers of dirt and dust but practically intact, were taken from the attic; and truckloads of them were transported to Paris.

Favand’s mission is to safeguard, protect, restore and integrate fairground heritage and also to bring it back to life with multimedia shows that combine the old with the new.

And so the museum team began restoring and documenting the objects salvaged from Ghent. It also started preserving the memory of the Van de Voorde family that had exhibited Théâtre Morieux for three generations.

This is when Erkki Huhtamo, a pioneering media archaeologist and professor at the University of California Los Angeles, a friend of Weynants, stepped into the picture.

Erkki Huhtamo begins the media archaeological excavations

Weynants had contacted his friend, telling him of the puzzling things he had discovered. Having visited Favand in Paris and seen the wealth of things he had acquired, Weynants urged Huhtamo to travel there to meet Favand and see the treasures. Weynants knew that Huhtamo had been working for years on a book on moving panoramas, the seminal work Illusions in Motion (2013).

As Weynants had discovered, the Théâtre had also presented moving panoramas, and some of the panoramic canvases on huge rolls remained more or less intact. There was also a considerable number of sketches and designs.

Huhtamo followed Weynants’s suggestion. He was astonished, returned several times, and gradually began collaborating with Favand to uncover the secrets of the long history of Théâtre Morieux. That also required working in German archives, where additional material could be found (part of the Van de Voorde family who exhibited Théâtre Morieux had lived in Bremen and used the “Hansastadt” as its base – at one point the family had two mechanical theatres on the road).

So began a major media archaeological excavation that has already spanned many years and still continues. Weynants has contributed along the way.

In the summer of 2018, together with the team of Musée des Arts Forains, Huhtamo reconstructed the auditorium and the fairground pavilion’s seating from the pieces stored at the museum’s attic.

Not only that. “We also found boxes of homemade flares that were hidden in the tiny weapons of the mechanical soldiers. These were then triggered during scenes of combat. Gunpowder was rolled in paper strips, cut from remnants of advertising posters,” Huhtamo says.

Besides the material remains of the theatre, the collection contains an extensive paper archive. Huhtamo classified the various documents: letters, invoices, receipts, official documents, business cards, photographs, notebooks, design sketches for marionettes, sketches for moving panoramas, loose handwritten notes and programme flyers, fairground organ catalogues, …

Particularly visually interesting are the postcards depicting fairground related and other popular attractions sent between fairground owners, for example between Morieux and colleagues such as Opitz. Slowly, Huhtamo realized that the fragments he took out from the cardboard boxes collected in Ghent did not only answer questions about Théâtre Morieux and its owners; they also bear the traces of something much more comprehensive.

Material heritage as a window into immaterial heritage

Théâtre Morieux travelled to many fairs and, as a result, became a material carrier of the cultural life in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It is a remnant of a form of popular culture and a (modest) witness of early capitalist exploitation.

But that is not all: this specific find tells us a lot about the gradual unfolding of media culture, which Huhtamo has been researching for a quite some time now. Even though fairground traditions are rooted in older forms of public rituals and practices, they were also a place where new media forms were introduced and tested. In many ways, the fair was a precursor of our current mediatized age.

The rediscovery of Théâtre Morieux de Paris is an extraordinary story of chance, opportunity, and determination. The examination of the findings sometimes resembles detective work. The researcher not only needs analytical know-how, but also social skills and a good nose. The preservation of a travelling theatre’s collection in its entirety is a highly unique phenomenon. But some pieces of the puzzle still need to be put together, while others remain missing.

The Arts & Media Archaeology research seminar with Erkki Huhtamo & Thomas Weynants took place on September 5, 2022, at Antwerp Research Institute for the Arts (University of Antwerp)

The core of the discovery is the dismountable fairground pavilion, which was 35 metres wide, 6 to 7 metres high (depending on the skyline), and 8,5 metres deep. Most of its elements, including the decorative facade and the auditorium with its seats, oil lamps, stage curtain and its mechanism, etc., still exist. The ticket booth and boxes of unsold ticket rolls survive as well. Even the ushers’ uniforms and red caps with the words “Théâtre Morieux” embroidered on them, remain. Musical instruments and sheet music remind us about the role of music and sound effects in the performances.

The central feature of the mechanical theatre were its mechanical marionettes, which Théâtre Morieux called “automats” (Automaten, automates). They are animated figures moving back and forth across the stage in front of a painted backdrop. Over six hundred of them survive, with sketches as well as cardboard mock-ups used as models when producing them. (…) The figures have been cut out of tin sheet and painted in vivid colours, using “illusion painting” technique. They were often painted from both sides so that they can move to both directions. Ingenious mechanisms of wooden and copper parts allow then to move along rails one after another; the motive power is provided by turning a hand crank.

Another medium that was often part of the program was the moving panorama (called “cyclorama” in the Théâtre Morieux publicity). The notion refers to long roll paintings that moved horizontally past the audience’s eyes by means of a mechanical cranking system. At least four moving panoramas exhibited by Théâtre Morieux survive. They were found wound on huge rolls of canvas, each 90 metres long. A panorama of the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900 (60m) and one depicting the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905 (30m) had been stitched together. Two other 90 metres long rolls each contain an elaborate travelogue. “The Morieux panoramas belong to the most impressively painted and best-preserved surviving examples”, according to Erkki Huhtamo.

On the moving panorama, see Huhtamo’s Illusion in Motion: Media Archaeology of the Moving Panorama and Related Spectacles (MIT Press, 2013).

On the illusion painting technique, see Bruno Forment’s Droomlanders: Tovenaars van het geschilderde toneeldecor (Davidsfonds, Standaard uitgeverij nv en CEMPER, 2021).

Author

-

Nele Wynants is research professor art and theatre studies at the University of Antwerp (Antwerp Research Institute for the Arts - ARIA). She coordinates the EU-funded project Science at the Fair: Performing Knowledge and Technology in Western Europe, 1850-1914 and is editor-in-chief of FORUM+ for research and arts.