It might be hard to image for generations that grew up with the Sinksenfoor, but 150 years ago, people could learn something new at the yearly funfair. With her project Science at the Fair, Nele Wynants and her team research how itinerant showpeople and museums played an important role in the circulation and popularization of science, knowledge, and visual culture. In so-called anatomical cabinets, zoological and anthropological museums and scientific theatres, itinerant showpeople demonstrated “wonders of nature” and spectacular scientific developments at the annual funfair.

Your research is at the intersection of science, theatre, and media. Where did your fascination for this crossover originate?

Many of today’s most evident technologies and media stem from theatre or popular culture, just consider lighting and electricity. Artists have always been quick to experiment with new media, such as projection techniques. From the magic lantern to cinema: it all started before the eyes of a live audience.

Additionally, the theatre – and by extension the fair and other public venues – were the place to experience new technologies and scientific developments during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Science communication and popularization have been around for quite some time. In the past, it was circulated in theatres, parish halls, and itinerant museums by itinerant lecturers and showpeople who called themselves ‘doctors’ or ‘professors’ and gave electricity, astronomy, or microscopy demonstrations. Combining a microscopy with a projection device, something as minuscule and invisible to the naked eye as a louse, wings of a fly or the bacteria in a drop of water could be abundantly magnified.

In short, the histories of science, theatre and media are very much intertwined, even if we often remain unaware of it.

Recently, you received an ERC starting grant for "Science at the Fair: Performing Knowledge and Technology in Western Europe, 1850-1914". Where did the idea for this research project start?

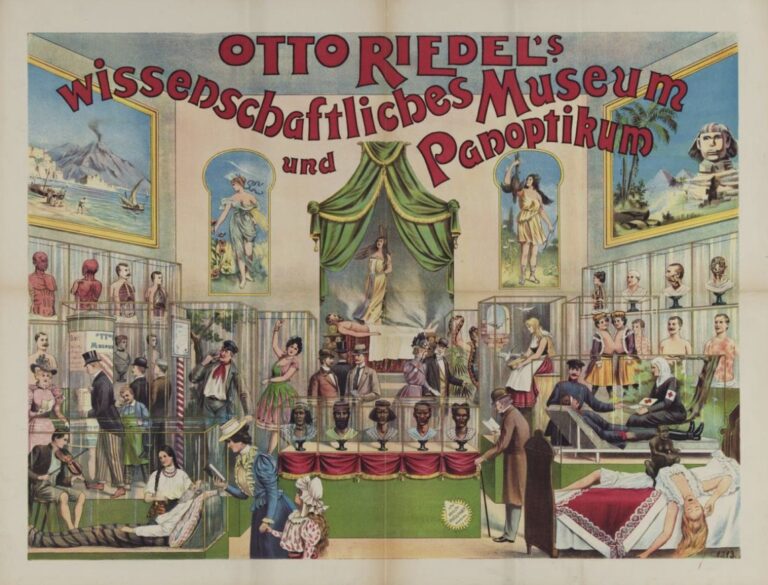

The idea for Science at the Fair evolved from previous research into visual media and theatre technology, more specifically in so-called ‘scientific theatres’. I noticed that many of those theatres crossed national borders and often performed at markets and fairgrounds. They were staged among mobile scientific museums on anatomy and natural history. Wax figures provided audiences with insights on anatomy and biology; and even depicted historical and/or religious scenes.

I realized there was little research or sources on the subject. Existing literature was usually focused on local events, such as the Bruges or Walloon fair, which overlooks the international appeal of artists who toured a very extensive area.

The SciFair project studies in which way these itinerant artists and showpeople contributed to a new culture of knowledge between 1850 and 1914. At a time when modern means of communication were still in their infancy and only a minority of the population could read, many relied on these itinerant shows and exhibitions to find information.

The project starts from the hypothesis that, during this time period, funfairs were not merely local folklore or folk tradition, but also hubs of international exchange in which itinerant entertainment played a central and modernizing role in the dissemination and popularization of science and knowledge, for people from across the social spectrum.

Showpeople relied on very efficient international networks. We want to map out precisely these transnational relationships of Western European fairground theatres.

We will also analyse how implicit knowledge and social values about, for instance, health, gender, nation, class or ethnicity were spread in this way. As we need to interpret this popular and spectacular culture against the background of our colonial history.

What is your personal favourite among the discoveries you’ve made so far?

I delight in serendipitous and unexpected findings, and I rely quite heavily on my intuition when following a particular lead. This seems at odds with the methodologies expected of scientists, but often things or people suddenly cross your path and turn out to be important for the course of your research. If you are open to these kinds of unexpected twists, you sometimes make the most interesting discoveries. That may sound romantic and naive, but this mindset has often yielded quite interesting results.

Interpersonal contact is crucial as well. When you talk to collectors who want to share their passion, or are joined in your search by a librarian or archivist you’ve persuaded into going the extra mile, you sometimes stumble onto data, opening up stories you never would have found otherwise.

Recently, I was at a second-hand bookstore in Paris and enquired about certain titles with the shop owner, while at the same time elaborating on my project. Another customer was listening in. Coincidentally, he knew some fairground people in France and Germany (communities that are incidentally fairly closed, and difficult to access) that he could put me in touch with. He insisted that I open my Facebook app on the spot and send out some friend requests, accompanied by his regards, right then and there. I only know this person’s first name, yet it was one of the most productive experiences within my research. Thanks to him, I am in touch with some people that would be very interesting to interview. Oral sources like these are incredibly valuable, since the funfair is a form of intangible cultural heritage. Speaking of which, did you know that an application is currently underway to have the fairground culture of Western Europe recognized by UNESCO as intangible heritage?

Authors

-

Michelle Coenen is the communications officer for the Faculty of Arts at the University of Antwerp. She is also an editor-in-chief at Bladspiegel, the faculty's blog with a focus on research in the area of philosophy, history, culture and language.

-

Nele Wynants is research professor art and theatre studies at the University of Antwerp (Antwerp Research Institute for the Arts - ARIA). She coordinates the EU-funded project Science at the Fair: Performing Knowledge and Technology in Western Europe, 1850-1914 and is editor-in-chief of FORUM+ for research and arts.