At a time when few Europeans travelled to the African continent, the public stilled their curiosity for what happened in the Congo Free State by listening to the travel stories of European explorers. How was the colony represented in Belgium between 1885-1945? This is the key question of Anse De Weerdt’s PhD research. In the following, she will tell us where her quest began.

Whenever I visited my grandfather, he would eagerly show his collection of old cameras, which he collected as a hobby photographer. On his dresser, he flaunted three magic lanterns. These three pieces in his collection looked strange to me as a child. I didn’t quite understand what they were, but I enjoyed watching my grandfather passionately show off the curious objects.

Now, many years later, the magic lantern is the protagonist in the research I am conducting as part of the B-magic project. Though I unfortunately can no longer tell him that. I now know that the magic lantern has told many vivid stories, many histories, and is therefore a rich object of research.

The lantern as a popular mass medium

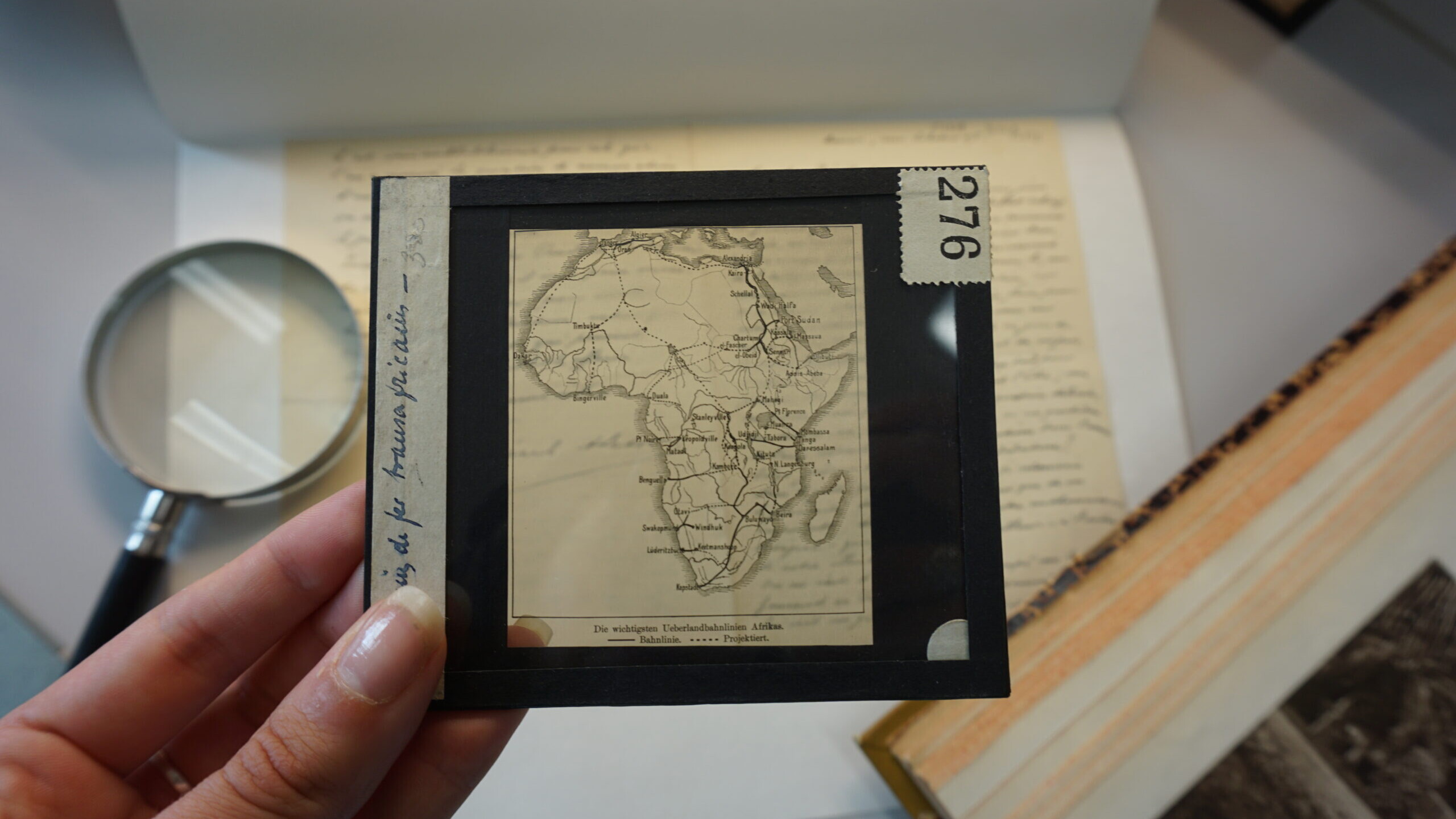

The magic lantern is a device that was developed in the seventeenth century for the projection of images for a live audience. Initially hand-painted but later printed, photographic images on glass slides appeared enlarged on a screen to illustrate a lecture or story. Since the late nineteenth century, it became extremely popular in all branches of society and was used for various purposes: entertainment, education, and political and religious propaganda. Even though the magic lantern was present in many public and private domains until deep into the twentieth century, it has been a largely overlooked medium in media history, often treated as a less developed ancestor of cinema.

Pictures of Congo in Belgium

As one of the first global mass media, the magic lantern played an important role in the colonial practices of state officials, missionaries, and scientific and academic communities. Since the end of the nineteenth century, the lectures of these explorers, scientists, missionaries were accompanied by travel photographs taken with a portable Kodak camera. This was the standard equipment for about anyone travelling within the colonies.

After returning home, the travellers turned their photographs into magic lantern slides. They were inserted in a magic lantern with a light source, allowing photographs of faraway territories to be projected on a large screen for the curious people at home.

Many questions left

There are still many unanswered questions: Who gave those lectures? How did these lantern images shape ideas about the colonies and their inhabitants? What is the impact of the colonial lantern representation on current discourses in visual media and on Belgium’s colonial heritage? Which political and religious values and ideas circulated in these representations?

In my PhD project entitled “Travelling colonial pictures: Circulation of colonial magic lantern images between science, politics, and religion” I aim to uncover the role of colonial magic lantern lectures in Belgium between 1885-1950. The goal is to unravel the entangled relation between science, politics, and religion in the Belgian colonial context. To do so, I analyse the public speakers’ discourses in relation to the colonial slides used to illustrate their stories. I will follow them on their journeys as they visited different sites within academical, geographical, scientific, economic, and medical societies.

I am only at the beginning of my search, but regularly think back to my grandfather. What would he think of all this? No doubt he would be as impassioned as me or even want to go exploring with me.

Anse De Weerdt’s research is funded by Le Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique – FNRS in the framework of the Excellence of Science project B-magic (EOS-contract 30802346).

Author

-

Anse De Weerdt's master's thesis in History at the University of Antwerp (2021) focused on Belgian solidarity with Palestine in the 1960s and 1970s. She is now a joint PhD student at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB) and the University of Antwerp (UAntwerpen) on the B-magic project with her research “Travelling colonial pictures: circulation of colonial magic lantern images between science, politics, and religion in Belgium (1885-1950).”